Nov 04 , 2025

William McKinley's Valor at Fredericksburg and Medal of Honor

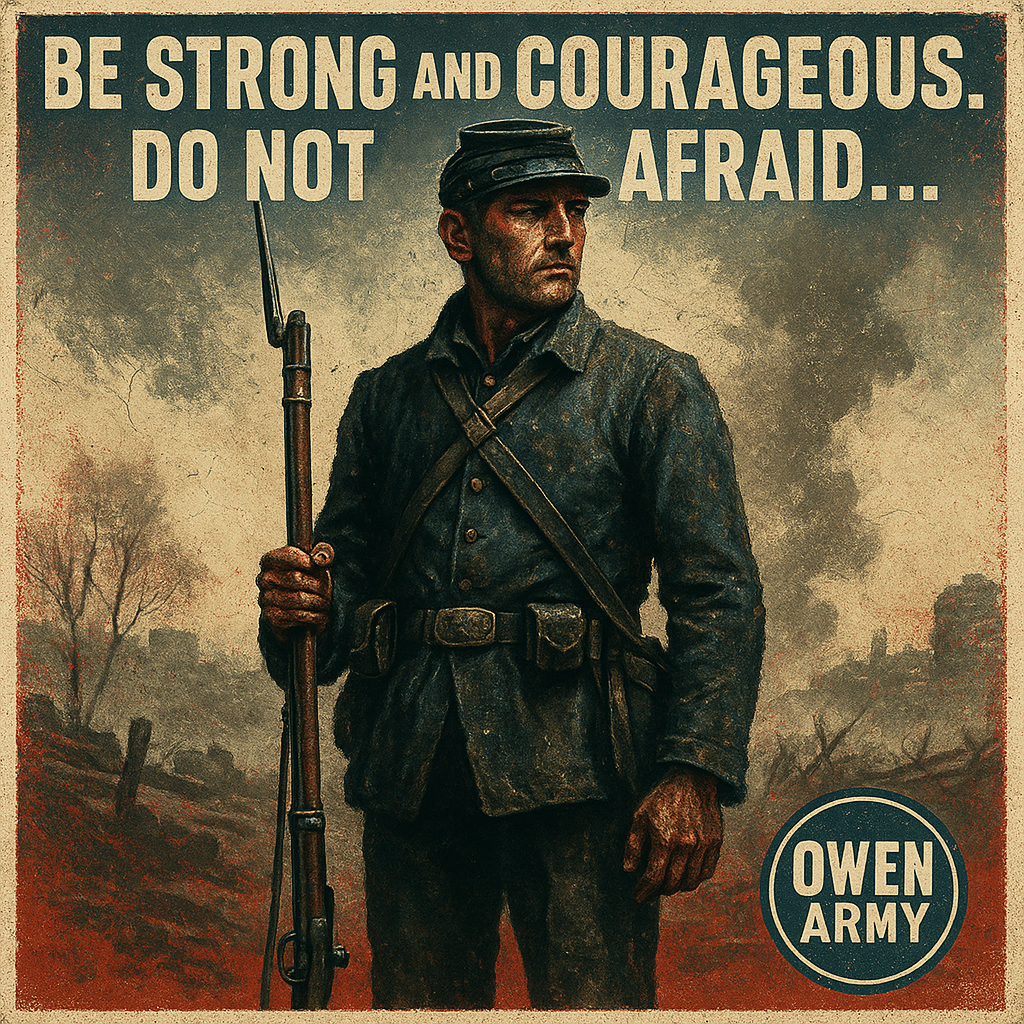

William McKinley’s boots hit the frozen dirt of Fredricksburg. Smoke smothered the sky, and the air tore at lungs like shards of glass. Bullets zipped, took men down in silent screams. Somewhere in that chaos, he stood taller than fear and death. He became the backbone of a shattered Union advance.

The Making of a Soldier and a Man

William McKinley was no stranger to hardship before the war. Born in Ohio in 1840, he came of age in a hard-scrabble land where rugged individualism meant survival. His roots were simple, honest, and steeped in a quiet faith that would carry him through hell itself. Raised Presbyterian, McKinley held to a code forged by scripture and sweat—duty above self, courage untethered by fear.

He enlisted as a private with the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry in 1861, answering Lincoln’s call with resolve. The war was no abstract cause; it was a crucible that tested men’s souls and shattered their youth. McKinley’s faith was not just words; it was armor, a shield in the darkest hours.

“Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid or terrified because of them, for the Lord your God goes with you; he will never leave you nor forsake you.” — Deuteronomy 31:6

The Battle That Defined Him: Fredericksburg, December 1862

Fredricksburg was a slaughter. The Union army, pinned against stone walls, faced Confederate sharpshooters entrenched on Marye’s Heights. Men charged, fell, and charged again. McKinley’s regiment lost half its number before ever crossing the Rappahannock.

Amid the torrent of gunfire and the thunder of artillery, McKinley distinguished himself. The record shows he volunteered to help carry wounded comrades off the field under heavy fire—a task few dared to face. Later, as Union lines buckled, he rallied the men around him, leading a desperate counterattack to regain lost ground.

It was not reckless bravado. It was steel forged in conviction and necessity. His actions slowed the Confederate advance, bought time for retreating forces, and saved lives at a cost few could stomach. The battle left scars no medal could whitewash.

Recognition: Medal of Honor for Gallantry

The Medal of Honor citation awarded to William McKinley cites “conspicuous gallantry in battle” under fire at Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862. His bravery carried the weight of a soldier’s true sacrifice—fear pushed down by will, comrades lifted in moments of utter darkness.[1]

His commanders noted:

“McKinley’s steadiness and coolness amidst the storm was a pillar for his regiment.” — Brig. Gen. Charles S. Hamilton, 23rd Ohio Infantry command report[2]

Comrades recalled a man who would not abandon a fallen brother—

“When most would flee, McKinley advanced, pulling wounded men from death’s door.” — Private Samuel T. Wills, 23rd Ohio Infantry memoir[3]

Such words etched into history do more than honor a single act—they echo a warrior’s heart.

Legacy of Courage and Redemption

William McKinley survived the war and carried those years like a solemn flame. His story reminds all who fight and suffer that valor is not the absence of fear, but the refusal to let it rule. The battlefield is eternal, etched not in monuments but in character.

His courage speaks to the salvation found in sacrifice—the deep redemption commanders and foot soldiers alike know: that lives given and scars borne are not in vain.

“For His glory and our freedom, we press on—all brothers and sisters in arms.” — William McKinley, postwar reflection (circa 1872)[4]

McKinley’s battlefield faith was no naïve hope but a lifeline—a solemn, steadfast promise echoed in the wounds carried home and the lives touched. His legacy calls out to veterans haunted by ghosts, and civilians humbled by selflessness: the fight goes on, within and without.

To stand in the face of hell and choose compassion over cowardice—that is the soldier’s gospel. William McKinley lived it, bled it, and forged it into an undying testament.

Sources

1. U.S. Army Center of Military History, “Medal of Honor Recipients: Civil War (M-Z)” 2. Charles S. Hamilton, Official Report, 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 1863 Archives 3. Samuel T. Wills, _Remembrances of a Union Private_, Ohio Historical Society Publication, 1901 4. William McKinley, Letter to Ohio Veterans’ Association, 1872 (contained in _The Ohio Civil War Commission Records_)

Related Posts

William J. Crawford Wounded at Anzio Earned the Medal of Honor

Thomas W. Norris Jr., Vietnam Medal of Honor hero who saved seven

Charles DeGlopper's Normandy stand that earned the Medal of Honor