May 17 , 2022

'Black Death' received Medal of Honor 95 years late: fought off dozens of enemy despite being shot 20 times

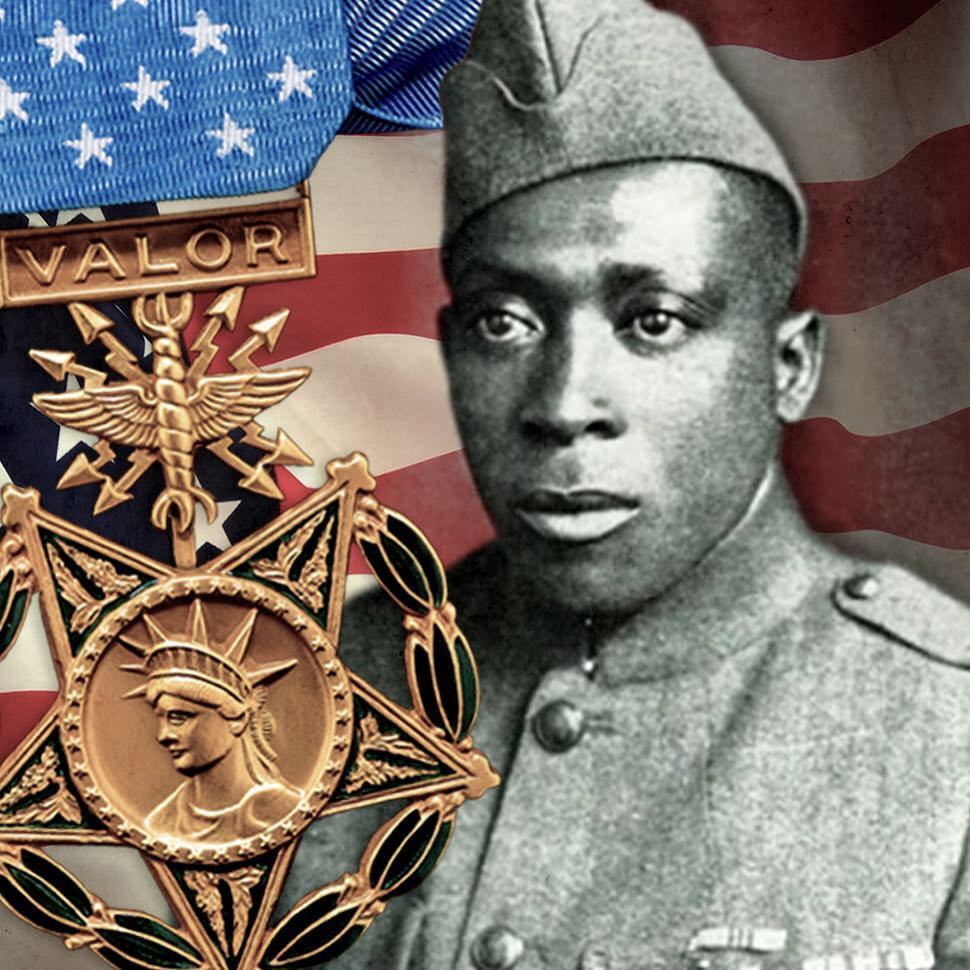

Army Sgt. Henry Johnson was part of the 369th Infantry Regiment — the Hellfighters from Harlem — which originally was composed of New York National Guard soldiers. This photograph was taken as the ship carrying the regiment returned to New York City in 1919. An all-black combat unit, the 369th fought under French command in World War I. (New York State Military Museum photograph)

He was 26 years old, 5-foot-4, weighed 130 pounds and came from Albany, N.Y.

And, on the night of May 15, 1918, then Army Pvt. Henry Johnson, a member of the all-Black New York National Guard 369th Infantry Regiment, found himself fighting for his life against 20 German soldiers out in front of his unit’s trenchline.

Johnson fired the three rounds in his French-made rifle, tossed all his hand grenades and then grabbed his Army-issue bolo knife and started stabbing.

He buried the knife in the head of one attacker and then disemboweled another German soldier.

“Each slash meant something, believe me,” Johnson said later. “There wasn’t anything so fine about it … just fought for my life. A rabbit would have done that.”

By the time (what a reporter at the time called) “The Battle of Henry Johnson” was over, Johnson had been wounded 21 times and had become the first American hero of World War I.

Army Sgt. Henry Johnson waves to well-wishers during the 369th Infantry Regiment march up Fifth Avenue in New York City on Feb. 17, 1919, during a parade welcoming the New York National Guard unit home. Johnson was the first American to win the French military’s highest honor during World War I. (National Archives photograph)

Johnson’s actions that night brought attention to the African-American doughboys of the unit — the New York National Guard’s former 15th Infantry, redesignated the 369th for wartime service.

The 369th Infantry, detached under the French 4th Army’s command, arrived on the front-line trenches in the Champagne region of northeastern France on April 15, 1918. They were relieved to be free of the supply and service tasks of the past months and ready to join the fight.

The American Expeditionary Forces detached the regiment to bolster an ally and preserve racial segregation in the American command. The French welcomed the regiment that would earn its nickname as the “Hellfighters from Harlem.”

Fought by only two Soldiers, the regiment’s first battle would otherwise be a footnote in World War I history if not for the scrutiny the all-Black regiment faced at the time.

After weeks of combat patrols, raids and artillery barrages, Johnson and his buddy, Pvt. Needham Roberts, 17, of Trenton, New Jersey, stood watch near a bridge over the Aisne River at Bois d’Hauzy during the night of May 15.

This display in the New York State Capitol’s War Room highlights the military career of Sgt. Henry Johnson, a New York National Guard soldier who received the Medal of Honor on June 2, 2015, to mark his heroic World War I actions. On display are Johnson’s Medal of Honor, a French helmet similar to one worn by members of the 369th Infantry Regiment, an Army-issued bolo knife, a 369th Infantry Regiment patch and the regiment’s flag. (New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs New York Division of Military and Naval Affairs photograph)

An enemy patrol with 20 to 24 troops was determined to eliminate the outpost and take prisoners back to learn about the American force.

Around 2 a.m., shots rang out and the sounds of wire cutters alerted the two American Soldiers. Johnson, opening a box of grenades, told Roberts to run back and alert the main line of defense. But at that moment, the first enemy grenades landed in their position.

Johnson stalled the German patrol with grenades of his own as Roberts was struck down with shrapnel wounds to his arm and hip. When out of grenades, Johnson took up his French rifle.

“The Labelle rifle carries a magazine clip of but three cartridges,” noted Arthur Little, the 1st Battalion commander, in his 1936 book “From Harlem to the Rhine.”

“Johnson fired his three shots — the last one almost muzzle-to-breast of the German bearing down upon him. As the German fell, a comrade jumped over his body, pistol in hand, to avenge his death. There was no time for reloading. Johnson swung his rifle round his head, and brought it down with a thrown blow upon the head of the German. The German went down, crying.”

As Johnson looked over to assist Roberts, he saw two Germans lift him up to carry him off toward the German lines.

“Our men were unanimous in the opinion that death was to be preferred to a German prison,” Little wrote. “But Johnson was of the opinion that victory was to be preferred to either.”

Johnson reached for his bolo knife and charged. His aggressiveness took the Germans by surprise.

“As Johnson sprang, he unsheathed his bolo knife, and as his knees landed upon the shoulders of that ill-fated Boche, the blade of the knife was buried to the hilt through the crown of the German’s head.”

The Army adopted the bolo knife from its experience in the Philippine Insurrection of 1899. The big knife, used by Philippine insurgents, was heavily weighted along the back of its curved blade, and was devastating for close-quarter combat.

Turning to face the rest of the German patrol, Johnson was struck by a bullet from an automatic pistol, but continued to lunge forward, stabbing and slashing at the enemy.

The enemy patrol panicked, Little wrote. Overwhelmed by Johnson’s ferocity and with the sound of approaching French and American troops, the Germans ran back into the night.

“The raiding party abandoned a considerable quantity of equipment (from which estimate of strength of party is made), a number of firearms, including automatic pistols, and carried away their wounded and dead,” reported the New York National Guard annual report of 1920.

By daylight, the carnage was clear. Even after suffering 21 wounds in hand-to-hand combat, Johnson had stopped the Germans from approaching the French line or capturing his fellow Soldier.

“He killed one German with rifle fire, knocked one down with clubbed rifle, killed two with bolo, killed one with grenade, and, it is believed, wounded others,” the National Guard report said.The French 16th Division, which commanded the Hellfighters, quickly recognized the actions of Johnson and Roberts. The two Soldiers received the Croix du Guerre, France’s highest military honor.

The French orders, dated May 16, state Henry Johnson “gave a magnificent example of courage and energy.”

They were the first U.S. Soldiers to earn this distinction, and Johnson’s medal included the coveted Gold Palm for extraordinary valor.

From that point on, Johnson was known as “Black Death.”

The regiment would go on to prove itself in combat operations through the rest of the war, receiving the Croix de Guerre for the unit’s actions and 171 individual decorations for heroism.

Johnson would be singled out for his heroism and actions under fire. Former President Theodore Roosevelt called Johnson one of the five bravest Americans to serve in World War I.

The question of whether the African-American 15th New York Infantry would fight as well as any other unit was answered in the darkness of May 15, 1918.

After the war, Johnson and Roberts returned home as national heroes. Promoted to sergeant, Johnson led the New York City parade for the 369th in February 1919.

Johnson’s extensive injuries, however, prevented his return to any normal civilian life. He had difficulty finding work. He died destitute in 1929 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Some 97 years after his combat service, the Defense Department reviewed Johnson’s records and recommended him for the Medal of Honor. It was presented by President Barack Obama in 2015.

“We are a nation — a people — who remember our heroes,” Obama said during the Medal of Honor ceremony at the White House. “We never forget their sacrifice, and we believe it’s never too late to say, ‘Thank you.’”

Related Posts

Jacklyn Lucas, Medal of Honor Marine Who Saved Comrades at Iwo Jima

Alonzo Cushing’s Valor at Gettysburg and His Lasting Legacy

Henry Johnson Harlem Hellfighter Who Saved His Unit in WWI

5 Comments

JHGDMFC what a badass! It’s disheartening that it took almost a century to finally recognize this soldier for his bravery and courage under fire. I only served in the Army for 6 years, including a tour in Iraq and made the best friends a man could possibly hope for, but I am honestly ashamed of how black people were treated even as recently as the Korean conflict. They have shown time and time again how brave and capable they are as soldiers as far back as the Revolutionary War, and still my beloved country treated them as second class citizens. I served with people of color that I would to this day gladly lay down my life to protect, and the fact that SGT Harrison died broke and destitute is a stain upon my country. I can only hope that we will continue to do better and honor our country’s heroes, no matter their ethnicity or social status.

There are far too many instances of the heroics of soldiers falling through the cracks of military protocols and politics. It’s great to ‘finally’ award him this distinction, but it should have been much sooner. Former President Theodore Roosevelt called him one of the five bravest Americans to serve in WW1. It’s a shame he didn’t look further into Johnson’s record. We can only speculate as to why he didn’t, so a conversation on that subject would be moot.

What I, also, find distressing is that he died destitute and probably alone. We see the same happening to our veterans, today and it is truly a shame.

Give the man his due, He sounds like one hell of a soldier to me.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoFy6mNtdpo

The Germans in 1918 were not Nazis; Nazism did not exist at this point in history.

Please correct this utterly inaccurate title.